The Liver Life Project

Liver Transplant

So, you’ve had the Varices and that’s been taken care of…. For the time being. You’ve gone through the Ascites, and that’s being drained off every few weeks.

The Hepatic Encephalopathy is getting worse and is driving you and the family to despair. You’ve had five tumours,

three of which have been burnt off using the

ablation procedure. You’ve now got type 2 diabetes and you’re having to check your blood sugars four times a day, and inject yourself with insulin twice a day.

If that wasn’t enough, your overall general health is

going downhill fast. Your life clock is now ticking,

and those tiny grains of sand are seeping through the hourglass of your life. After all you’ve gone

through, there’s still one big problem you’ve yet to somehow overcome. For me, that one big problem

was an immense feeling of unworthiness and guilt.

After all, I was the one who caused all this to happen,

not anyone else. No one forced that drink down my throat. So, I had brought this all upon myself, and

I felt I had to suffer the consequences. Fortunately for us all, there’s one final chance. There is the

possibility of a Liver Transplant. But even going down this road is full of uncertainties.

Firstly, this is a gift and not

a right. There are people out there in need of a transplant through no fault of their own, i.e. Steatosis or Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis.

The liver transplant list doesn’t discriminate; it goes on availability, match suitability and other factors,

like how urgent your need is.

But before any of this can start, there are certain criteria and conditions that a person has to meet before they’ll be accepted onto the waiting list. The NHS has a

very strict code of practice about this:

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/liver-transplant/who-can-have-it/

Under UK regulations, you are usually only considered a suitable candidate for a liver transplant if you meet two conditions:

• Without a liver transplant, your expected lifespan would likely be shorter than normal, or your quality of life would be so poor as to be intolerable.

• It's expected that you have at least a 50% chance of living at least five years after the transplant with an acceptable quality of life.

Transplant centres use a scoring system to calculate the risk of a person dying if a transplant isn't performed. In the UK, the system is known as the United Kingdom

Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (UKELD). This is based on the result of a series of

four blood tests that create an average score. The higher you’re UKELD score and

your risk of death, the higher up the waiting list you will be.

Assessing your quality of life

Assessing your quality of life can be a subjective process. However, the following symptoms represent a decline in quality of life that many people would find

intolerable:

• persistent tiredness, weakness and immobility

• swelling of the abdomen, caused by a build-up of fluid (ascites), that doesn't respond to treatment

• persistent and debilitating shortness of breath

• damage to the liver that affects the brain (hepatic encephalopathy), leading to mental confusion, reduced levels of consciousness and, in the most

serious of cases, coma

• persistent itchiness of the skin

Estimating survival rates

The assessment of your likely survival rate is based on:

• your age (some transplant centres say that 65 years of age is the cut-off age)

• whether you have another serious health condition, such as heart disease

• how likely a donated liver would remain healthy after the transplant

• your ability to cope (physically and mentally) with the effects of surgery and the side effects of immunosuppressant medication

Tests will also be carried out to assess your health and your likelihood of survival. This can include examining your heart, lungs, kidneys and liver, as well as checking for

any signs of liver cancer.

Who can't have a liver transplant?

Even if you meet the above criteria, you may not be considered for a transplant if you have a condition that could affect the chances of success.

For example, it's unlikely that you will be offered a liver transplant if you have:

• Severe malnutrition and muscle wasting

• An infection – it would be necessary to wait for the infection to pass

• AIDS (the final stage of an HIV infection)

• A serious heart and/or lung condition, such as heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

• Serious mental health or behavioural condition that means you would be unlikely to be able to follow the medical recommendations for life

after a liver transplant

• Advanced liver cancer – by the time cancer has spread beyond the liver into surrounding tissue, it's too late to cure the cancer with a transplant

Additionally, a liver transplant will not be offered if you continue to misuse alcohol or drugs. Most transplant centres only consider a person for a transplant if

they haven't had alcohol or used recreational drugs for at least six months.

Types of liver transplant

There are three main ways a liver transplant can be carried out:

• Deceased organ donation – involves transplanting a liver that has been removed from a person who died recently.

• Living donor liver transplant –a section of liver is removed from a living donor; because the liver can regenerate itself, both the transplanted

section and the remaining section of the donor's liver can regrow into a normal-sized liver.

• Split donation – a liver is removed from a person who died recently and is split into two pieces; each piece is transplanted into a different person,

where they will grow to normal size.

Most liver transplants are carried out using livers from deceased donors.

Waiting for a liver

There are more people in need of a liver transplant than there are donated livers, which means there is a waiting list. The average waiting time for a liver transplant is

145 days for adults and 72 days for children. While you're on the waiting list, you will need to keep yourself as healthy as possible and be prepared for the transplant

centre to contact you at any moment, day or night. You should also keep the transplant centre informed about any changes in your circumstances, such as changes in

your health, address or contact details.

Life after a liver transplant

Your symptoms should improve soon after the transplant, but most people will need to stay in the hospital for up to two weeks. (I was in for a total of nine days.)

Recovering from a liver transplant can take a long time, but most people will gradually return to many of their normal activities within a few months. You'll need

regular follow-up appointments to monitor your progress, and you'll be given immunosuppressant medication that helps to stop your body rejecting your new liver.

These usually need to be taken for life.

Risks of a liver transplant

The long-term outlook for a liver transplant is generally good. More than nine out of every 10 people are still alive after one year, around eight in every 10

people live for at least five years, and many people live for up to 20 years or more. However, a liver transplant is a major operation that carries a risk of some

potentially serious complications. These can occur during, soon after, or several years after the procedure. Some of the main problems associated with liver

transplants include:

• Your body is rejecting the new liver.

• Bleeding (haemorrhage)

• The new liver is not working within the first few hours (primary non-function), requiring a new transplant to be carried out as soon as possible.

• An increased risk of picking up infections.

• Loss of kidney function.

• Problems with blood flow to and from the liver.

• An increased risk of certain types of cancer – particularly skin cancer.

There is also a chance that the original condition affecting your old liver will eventually affect your new liver. I would also like to point out that some people can go on

to suffer from mental health issues. These can include “

Survivor’s

Guilt” and PTSD. I suffered from “Survivor’s Guilt” for over ten months. There is sadly little or no help

available out there within the local communities.

Survivor’s Guilt

The Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham

The Queen Elizabeth (QE) hospital is where I had my life-saving liver transplant carried out. It is also the home of Birmingham University, which is at the forefront of

liver research.

I was going to include here an American video of a liver transplant. But decided that this might not be suitable for some people. Here, a friend of mine, Mr Alan Hyde,

talks about his liver journey. Although his journey wasn’t alcohol-related, by the time a person gets to this stage with their liver condition, it doesn’t matter what the

cause was, as the associated medical conditions are all the same. Sadly, Alan is no longer with us. He passed away due to kidney failure in September 2020.

This video also introduces a lovely new piece of kit called a liver perfusion machine. All is explained in this video. When this machine was first brought into service, it

was found that it placed an enormous amount of pressure on the stored blood reserves. Trials took place to try and use synthetic blood, but this didn't prove to be

very successful.

A word of warning

A person who ends up having alcohol-related liver disease has two battles going on. Firstly, there are the physical issues, like the damage being caused to the body,

and then there’s the mental issue too. If a person requires a liver transplant due to alcohol abuse, and hasn’t consumed any alcohol for over six months, but

continues to drink alcohol-free beers, wines, and spirits as an alternative, then they still won’t be considered suitable for a liver transplant, as the risk of relaps is

considered to be too big.

I

personally

struggled

with

“Survivor’s

Guilt”

following

my

liver

transplant

back

in

2016.

This

dark

cloud

lasted

for

10

months.

I

hate

to

admit

this,

but

I

did

harbour

suicidal

thoughts

at

times,

such

was

my

depressive

state.

I

can

certainly

see

how

others

would

reach

out

to

their

old

friend,

the

bottle,

in

an

attempt

to

lift

the

gloom.

Strangely

enough,

not

everyone

experiences

this

condition.

So,

much

more

research

into

this

condition

is

urgently

needed.

I

understand

that

post-liver

transplant

patients

have

a

much

higher

risk

of

suicide

than

any

other organ transplant, yet this doesn’t seem to be taken seriously enough.

Patients

should

be

encouraged

to

talk

more

openly

about

their

feelings

and

share

their

low

mood

experiences

with

their

partner,

spouse,

carer

or

even

online

support

groups.

They

need

not

suffer

in

silence,

as

this

is

all

part

of the healing process.

At

the

time,

I

would

feel

so

unworthy

of

this

second

chance

at

life.

I

was

63

when

I

had

my

transplant.

I

knew

back

then

that

a

newly

harvested

liver

could

be

split

and

shared

between

two

young

children

who

needed

a

liver

transplant.

They

had

their

whole

lives

in

front

of

them,

and

I

felt

that

with

me

having

this

liver,

I

was

denying

them

a

future.

I

felt

selfish

and

unworthy.

This

deep

feeling

of

guilt

would

bring

on

a

tearful

response

out

of

the

blue, for no other reason.

As

I

mentioned,

upon

discharge

from

the

hospital,

we

are

told

to

avoid

certain

places

of

prime

risk

from

airborne

infection.

GP

surgeries,

other

hospitals,

etc.

I

found

that

there

was

nowhere

to

turn

for

help

or

support.

Even

my

local “Mind” mental health charity had a six-month referral wait time.

I

happened

to

speak

with

one

of

the

then

hepatologists

at

the

QE

Hospital,

Birmingham,

about

this.

He

tried

to

help,

but

didn’t

really.

He

told

me

that

he

was

pleased

to

hear

this.

He

went

on

to

say

that

the

decision

to

offer

me

that

liver

was

his

and

that

he

was

glad

to

hear

that

I

felt

this

way,

as

it

told

him

that

I’d

never

abuse

alcohol

again and that he had made the right decision.

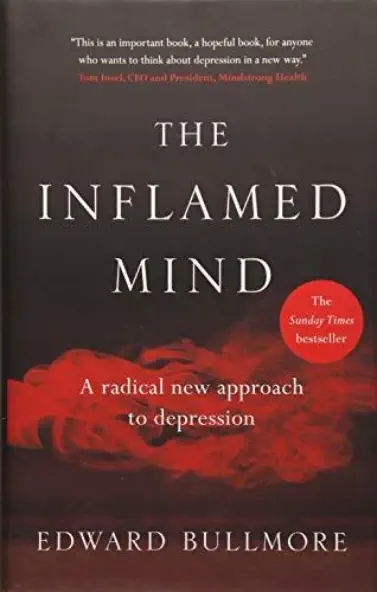

This

dark

cloud

went

on

for

about

10

months.

Until

I

happened

to

come

across

a

book

entitled

“The

Inflamed

Mind”

by

Prof

Ed

Bullmore.

(I

still

have

it

and

have

given

away

6

copies

over

the

years).

In

this

book,

Prof

Ed

explains

how

any

physical

assault

upon

the

body

will

cause

an

inflammatory

response

by

the

immune

system.

Here,

he

tells

of

how

cytokines

go

off

in

search

of

any

invading

bacteria

and

how

the

macrophage

cells

devour

these.

He

talks

of

how

it’s

been

discovered

that the cytokines can cross over the blood-brain barrier and alter a person's mental state.

Knowing this allowed me to understand that this depressive cloud and my emotional feelings were not of my own making, but due to a chemical response of the

operation by the immune system. In other words, these thoughts weren’t real. Understanding this gave me closure and allowed me to move on.

Two days after this realisation, that dark cloud was lifted.